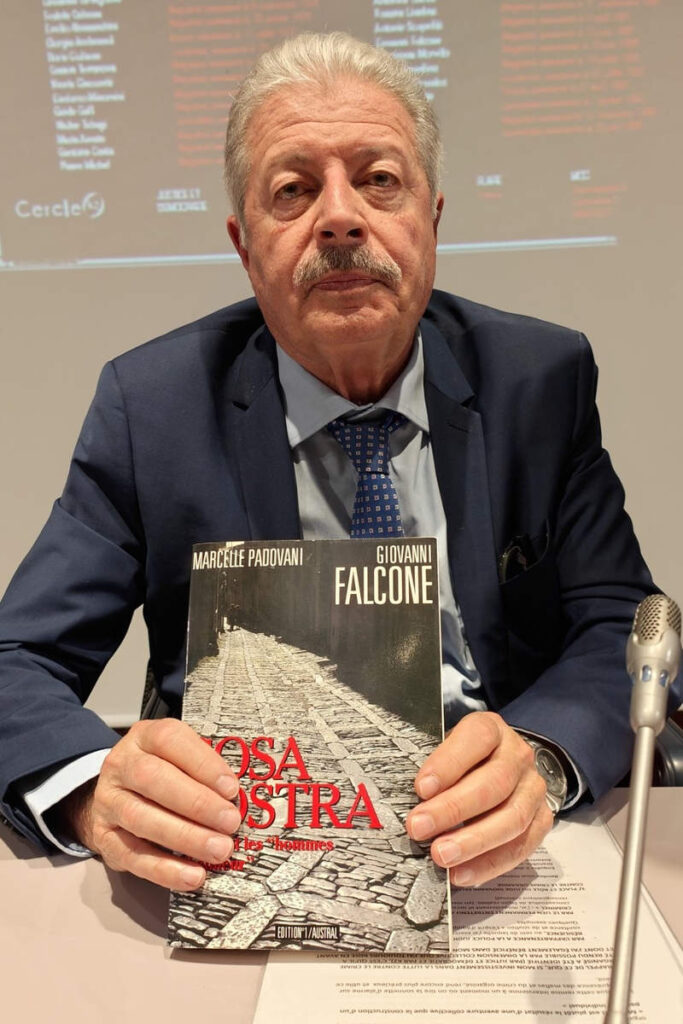

Michel Quillé, a former director of the criminal investigation department and former deputy director of Europol, has just been awarded the Giovanni Falcone 2024 Prize, which recognizes a professional working in the field of Mafia crime. Michel Quillé is now a security consultant. Interview.

What do you think needs to be done to combat organized crime in the future?

In my opinion, we need to focus our efforts in several directions. Firstly, to improve the fight against organized crime, criminal legislation needs to be better adapted. In 2024, when it comes to drug trafficking, France finds itself in the same situation as Italy in 1980: a lot of effort, some results, but nothing significant.

When Italy realized that its rule of law was unable to curb mafia activity, it simply set up a judicial system specifically for the fight against the mafia. This involved introducing the offence of mafia association, a system of repentance, a special prison regime and a system for seizing and confiscating mafia assets.

Over the past 15 years, France has improved its legislation against organized crime, but it has to be said that it has been overtaken by the widespread nature of organized crime.

The large sums of money generated by trafficking enable the heads of the networks, often based abroad, to continue to manage their teams of traffickers in France. These criminals sometimes even order the assassination of their competitors from their cells, and manage to corrupt potential witnesses at their trials. A debate on reforming this legislation would be possible if time allowed. I think it’s already too late to indulge in a psychodrama provoked by the introduction of special legislation.

Only such legislation could reduce the impact of the members of these criminal groups, be they dealers, spotters, nannies or “protectors”.

So what else can be done?

We need to step up the fight against the financial dimension of mafias: here too, progress has been made, notably with the creation of the AGRASC (Agency for the Management and Recovery of Seized and Confiscated Assets), but these measures need to be systematized and accelerated. We also need to invest more in the fight against the digital dimension of organized crime. France has made good progress, but we need to make this a priority, both in terms of trafficking (and not just drugs) and money-laundering mechanisms.

Are you concerned about the proliferation of mafias, which are increasingly taking the form of notables and white-collar workers?

In principle, organized crime aims to generate profits in any way it can. All forms of crime, whether drug trafficking, human trafficking, arms trafficking or waste disposal, generate large sums of money.

As a result, the profile of criminals has changed: they have almost inevitably become financiers. Although they do not manage the funds generated by their trafficking themselves, the financial volumes generated enable them to call on the assistance of specialists in taxation, accounting and capital transfers.

What has also become apparent to police officers in recent years is the multi-disciplinary nature of criminal organizations. To put it simply, they move from one traffic to another according to opportunities and expected profitability.

Worse still, this exponentially growing financial dimension enables corruption of public officials (police, court clerks) or in the private sector, such as port managers and stevedores.

What was your connection with Judge Falcone?

I had an indirect relationship with Judge Falcone, because during an investigation I led, I was led to question a member of the Sicilian mafia, whose mission was to distribute in Europe the quantities of cocaine sent to him by a Colombian cartel following an agreement between the two organizations.

During the interview with this Sicilian mafioso, he revealed to me that he was a relative of Tommaso Buscetta, who was himself described as the “great repentant”, and who, under the tutelage of Judge Falcone, had enabled the Palermo maxi trials to take place in 84-85.

Interested in the profile and revelations of the Mafioso I had arrested, Judge Falcone made a special trip to the Rhône-Alpes prison where he was being held to interview him.

As I had information that was not included in the minutes, it was planned that I should meet Judge Falcone to communicate it to him. For scheduling reasons, this meeting did not take place. But in the years following his conviction, having obtained repentant status, this mafioso was regularly debriefed in his French prison by one of Judge Falcone’s deputies.

But this missed appointment with Judge Falcone was not the last opportunity to work for him. One of the repentants he was treating, Antonino Calderone, revealed to him that a major Mafia boss had come to set up a Mafia family in Grenoble, the city where I was heading the judicial police at the time. As soon as I received this information, I put two measures in place. The first was a “Task Force” made up of police officers and members of the tax department to track down any possible financial infiltration by this Mafia family.

Secondly, I developed close cooperation with the Italian anti-mafia police force, the DIA (Direzione Investigative Antimafia), who, in addition to exchanging operational information, enabled me to discover and integrate anti-mafia working methods. Shortly afterwards, I was asked to set up an Antimafia Unit in France, given the positive results obtained previously.