That’s the question that 82-year-old Gilbert Thouvenin asks himself every day. His wife and three of his four children committed suicide, victims both of the little-known illness of bipolarity and of the wickedness of a family in their small village. Summary of his book “L’homme qui ne doit pas vieillir*” and interview.

But what kind of metal is this man made of? At the age of 82, Gilbert Thouvenin has endured some of the worst suffering on earth. The disease took his wife and three of his four children, all bipolar. They took their own lives. The hatred and jealousy of a few scoundrels in this small Lorraine village near Nancy undoubtedly aggravated their pathology. Gilbert’s family had to endure years of jealousy and harassment from evil-doers.

Criminal intent

One day, the brand-new combine no longer worked. The expert on site found that a malicious hand had slipped 3 kg of sand into the oil sump. The engine was dead. This sabotage was not isolated. Another day, the electrical and braking circuits of a truck were sheared off. The intent was criminal. The same year, pieces of steel were tied to corn cobs. They caused the forage harvester to explode. This happened two years in a row.

Not to mention the physical assaults, the most cowardly of which was undoubtedly that of Jean-Charles*, one of Gilbert’s sons, who was beaten with a crowbar by three village hooligans in the presence of the man who was to become… the commune’s mayor. Jean-Charles suffered several operations and unbearable pain as a result of a broken jaw and numerous wounds. Two years later, unable to bear the pain any longer, he took his own life.

He wanted to be a farmer

Nothing was spared for Gilbert, fatherless at the age of 2, raised the hard way by a courageous and loving mother. Thanks to an iron constitution, a character forged in hardship and a rare lucidity, Gilbert faced life with courage and determination. His entrepreneurial instincts did the rest. He wanted to be a farmer. He settled on a small farm that nobody wanted. By dint of hard work, he turned it into a fine operation. He became involved in the agricultural cooperative to the point of becoming one of the regional leaders in the field of agricultural machinery. Then he set up a highly successful transport company. At the same time, Gilbert built his home in the village. A beautiful home for his large family. Then another, then another. Today, Gilbert owns a portfolio of some 30 houses, 23 of which are rented out in the village. Which allows him to say he’s the village’s biggest taxpayer.

L’homme qui ne doit pas vieillir” (“The man who must not grow old”)

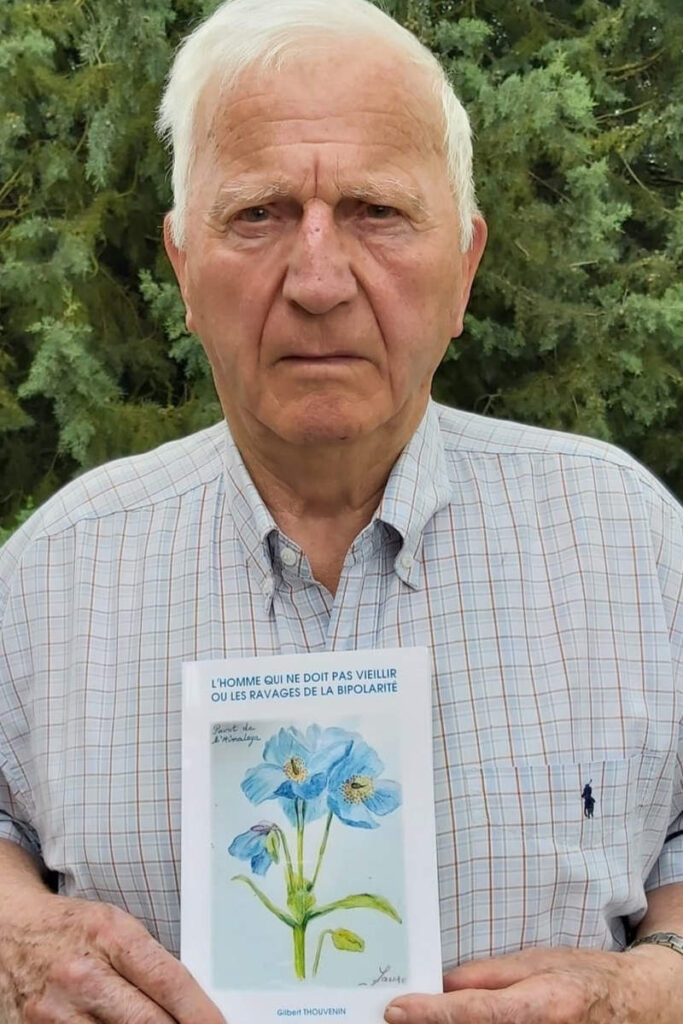

Gilbert Thouvenin tells his extraordinary story in a poignant self-published book entitled “L’homme qui ne doit pas vieillir où les ravages de la bipolarité*” (“The man who must not grow old or the ravages of bipolarity”). In fact, he tells the story of Georges, and has changed the first names of his wife and children. He never mentions the name of the mayor or the commune, so as not to expose himself to legal proceedings. Interview.

* “L’Homme qui ne doit pas vieillir ou Les ravages de la bipolarité”. By Gilbert Thouvenin. 22 euros. From the author. 06.17.62.85.13.

“It’s my duty to stay on my feet”

Why or for whom did you write this book? Is writing a form of therapy for you after so much misfortune?

I needed to bear witness. To bear witness to help those who are confronted with this kind of catastrophe in their family, i.e. bipolarity. Four suicides in one family is not a common occurrence.

I also wanted to leave the memory of all these things to my children, or whoever’s left, and my grandchildren. And no doubt for the generations to come, whom I won’t know but who will have the memory of my time on this earth and all the worries I had to overcome. They’ll know how I lived, what I fought for.

In the end, this is therapy for me. Because there are things that you don’t like to say when you’re talking to people, and which are easier to confide on paper.

Throughout this book, you talk about the ravages of bipolarity, which took the lives of your wife and three of your children. How would you describe this illness?

My wife was bipolar before I met her. She wasn’t accepted in her family, she was the child too many. There’s probably some secret about her birth that I haven’t been able to get to the bottom of. At the age of 17-18, the first signs of her illness appeared. She had to stop her studies. Our meeting and the prospect of a new life meant that the disease fell asleep inside her. It was a period of remission.

Bipolarity is a psychological illness. At the time, it was referred to as manic-depressive disorder. It manifests itself in three phases. The first phase is euphoria. The sufferer wants to do lots of things, sometimes spending money recklessly. In our case, this didn’t manifest itself too much, as I was the one keeping the accounts.

The second phase is a period of intense, violent excitement, whether verbal or even physical. This was the result of the fatigue that had built up during the euphoria. The third phase is depression. The patient collapses. He may sink to the bottom of the abyss. It’s during this period that suicide occurs, even if not all bipolar sufferers have suicidal thoughts.

Was this also the case for your children?

The genes passed on by their mother to her children appeared after their mother’s death. Up until then, they’d all been well-balanced and well-educated, even if they’d been upset by her illness. My wife had terrible fits, we were in a state of madness, we couldn’t really communicate with her. She would sometimes scream for hours. How can children and teenagers resist all that?

Was the bipolarity from which several members of your family suffered aggravated by the thousands of miseries inflicted on you in the little Lorraine village where you settled in the 60s?

It certainly did! Because illness creates fragility in the sufferer. He or she is even more affected by the frustrations. This creates a vicious circle. Even bipolar sufferers, for whom there are no major worries, also have crises, but they can stabilize. And when there are major upsets, the illness worsens. For my wife, it’s certain that the day I had all my equipment destroyed, when we were at a total financial impasse, when I had to take out major loans to get out of this predicament, for me it was one more struggle, but for her it was unbearable. During these periods, she had major crises and had to be placed in a psychiatric hospital.

Why is there so much hatred for you in this village? Because of your success?

As soon as I arrived in the village, I caused a stir. I was 20 years old, I didn’t know anyone here. I had no money. I borrowed money to buy animals and equipment. I quickly became jealous. People imagined that my in-laws, who belonged to the good landed bourgeoisie, were helping me financially. Which, alas, was not the case. I made people envious.

It started as soon as I settled in. They’d cut my park posts to release the animals. They’d block my path with a tractor when I went by with my cows. They kept an eye on me. When I say “they”, it’s mainly a family in the village who were against me. One fine day, we discovered that the combine harvester wasn’t working. An anonymous hand had slipped 3 kg of sand into the oil sump. The engine was dead. It was sabotage. That same year, I had prepared my truck to pass the technical inspection. I asked my son Jean-Charles (first name changed) to grease the transmission and joints. But when he went under the truck, he saw that everything had been sheared off during the night: the electrical circuit, the braking system, and so on. A tragedy was averted.

This is a criminal act…

There were other events. Like the introduction of very abrasive products into all the engines of the farm and the transport company. A large truck was destroyed, as was the farm’s main tractor. On the night of the sabotage, my son saw the perpetrator coming out of the shed. There can be no doubt. However, the gendarmes’ investigation was unsuccessful, even though it confirmed the presence of this abrasive in the engines.

Two years in a row, these sad individuals hooked pieces of steel, ploughshares, into the corn so that it would pass through the forage harvester. It exploded two years in a row. Completely wrecked. Thanks to the flexible wire around the piece of steel, I was able to trace it back to the perpetrators. The police found evidence of their involvement in sabotaging the forage harvester. They were the same evil characters.

Even more serious was the physical assault on your son, Jean-Charles, in 2008. What happened there?

It was a municipal election year. The mayor at the time didn’t want to run again. He organized a meeting to encourage residents who wanted to do so to form a list. I went with my son Jean-Charles. There was also the family who had been harassing me for years. In particular, my father, who we knew had been stripped of his civil rights a few years earlier. He was quick to express his interest in becoming mayor of the commune and offered to draw up a list. Jean-Charles then asked him to explain his loss of civil rights. This caused a stir in the audience. The interested party said “joker”. He didn’t reply. But at the end of the meeting, he approached Jean-Charles and said “You, you’ll pay for this”.

In the elections, this individual didn’t make it past the first round. In the second round, he was elected last on the list. But he managed to get himself elected 1st deputy because nobody else wanted the job.

On June 16, 2008, three members of the family – the 1st deputy, his brother and his son – cornered Jean-Charles in a field. They beat him to the point of breaking his jaw. He spent 10 days in hospital, where a metal plate was placed to consolidate the bones. He was left with permanent and irreversible neuralgia.

The assailants were convicted a few months later. But they appealed. Meanwhile, Jean-Charles committed suicide on April 21, 2020.

You’ve been an extraordinary entrepreneur. You created and developed a farm, then set up a transport company, became a manager in an agricultural cooperative, found time to build some thirty houses… all the while remaining a caring father to your four children. What kind of metal are you made of?

It was the circumstances in which I was brought up that made me what I am today. It’s the foundations. I was fatherless at the age of 2. My mother was exemplary. She would often say to us, “I promised your father that I would make men of you, and I will make men of you”. This demand was very important to me.

But I had to take matters into my own hands at a very young age. When I was 15 or 16, I had to stand up to the farmers in the village where I was born, when they abused my mother, whom they called “the widow”. I also took on farming responsibilities at a very young age. At 18, I was president of the Lunéville young farmers’ association. My youth gave me a cuirass. When I arrived here, in this village, I had to face problems that don’t usually arise for a 21-year-old. It’s through difficulty, struggle and self-sacrifice that you grow up, not in the easy way.

Your book is entitled “The Man Who Must Not Grow Old”. Why don’t you have to grow old?

Because I don’t have the right. I have grandchildren who need to have someone solid beside them. I have ten grandchildren. For me, it’s a duty not to grow old. I have to be there for them. Being up and about at 82 may be a matter of will, but it’s much more a matter of duty. I wanted a big family and I have to take care of it until my last breath.

Why did you change the first names in your book?

Writing in the third person is a way of talking about yourself without putting yourself forward in a pretentious way. I was also concerned, in my need to bear witness, to protect my family. Analyzing those who attacked me, those who judged me, those who betrayed me was easier for “Georges” (pseudonym) than for Gilbert. Changing names also saves me from legal proceedings.

Are you a believer?

I was brought up in a very Christian, religious family at a time when you weren’t supposed to ask questions. Anything that couldn’t be explained was classed as a “mystery”.

I’m in a period of doubt and questioning. I’ve often asked God to help me. I’ve asked him why he took them all away from me and why he deprived me of their love? On this tortuous road, why I had often found myself alone. I think he gave me the strength to tame my solitude, to make it an asset and not a weakness. I need to be strong for those who expect my support, but also for myself. Maintaining a social life, reaching out to others, is essential. I’ve visited over 40 countries around the world. It’s a duty for me and my children to stay on my feet.

Interview by Marcel GAY